Mike Johnson The Pope of the Evangelical Christian National Movement

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Mike Johnson the new King Daddy of Christian Nationalism Dominion Theology and Kingdom Building

Mike Johnson Says Americans 'Misunderstand' Separation Of Church And State (msn.com)

Separation of Church and State: A ‘misnomer’, says Mike Johnson (msn.com)

Prelude:

We must not be ignorant to these times and of this season dear Saints. Take a moment to read and meditate on 1 Thessalonians Chapter 5.

Background: Striving Lawfully

https://www.thethirdheaventraveler.com/2020/11/fight-good-fight-dear-christian-strive.html

King

king (n.)

a late Old English contraction of cyning "king, ruler" (also used as a title), from Proto-Germanic *kuningaz (source also of Dutch koning, Old Norse konungr, Danish konge, Old Saxon and Old High German kuning, Middle High German künic, German König).

This is of uncertain origin. It is possibly related to Old English cynn "family, race" (see kin), making a king originally a "leader of the people." Or perhaps it is from a related prehistoric Germanic word meaning "noble birth," making a king etymologically "one who descended from noble birth" (or "the descendant of a divine race").

Daddy

c. 1500, colloquial diminutive of dad, with -y (3). Slang daddy-o is attested by 1949, from bop talk.

"a father, papa," recorded from c. 1500, but probably much older, from child's speech, nearly universal and probably prehistoric (compare Welsh tad, Irish daid, Lithuanian tėtė, Sanskrit tatah, Czech tata, Latin tata "father," Greek tata, used by youths to their elders). Compare papa.

"a father, papa," recorded from c. 1500, but probably much older, from child's speech, nearly universal and probably prehistoric (compare Welsh tad, Irish daid, Lithuanian tėtė, Sanskrit tatah, Czech tata, Latin tata "father," Greek tata, used by youths to their elders). Compare papa.

"the Bishop of Rome as head of the Roman Catholic Church," c. 1200, from Old English papa (9c.), from Church Latin papa "bishop, pope" (in classical Latin, "tutor"), from Greek papas "patriarch, bishop," originally "father" (see papa).

Applied to bishops of Asia Minor and taken as a title by the Bishop of Alexandria c. 250. In the Western Church, applied especially to the Bishop of Rome since the time of Leo the Great (440-461), the first great asserter of its privileges, and claimed exclusively by them from 1073 (usually in English with a capital P-). Popemobile, his car, is from 1979. Pope's nose for "fleshy part of the tail of a bird" is by 1895. Papal, papacy, later acquisitions in English, preserve the original vowel.

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by a pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden seal (bulla) traditionally appended to authenticate it.

disclaimer: The Dissenter - the pot calling the kettle black

The Current Speaker of the House is a "so called Christian " saying America might be under God's Judgment how America needs to turn back to God... This fraud never speaks out against abortion according to this article.

Quote Speaker Johnson himself played a significant part in killing legislation that would end abortion in some states and hold those who commit this heinous evil accountable. Therefore, this period of judgment is a time for the Church to introspect, confront sin and error, and realign with biblical teachings.

It also is a lie that the Church is asleep 😴 and allows this to happen.

The Laodicean church is part of all this.

The true church is Philadelphia.

This Johnson fraud is also a major NAR DOMINION THEOLOGY believer. Wants the church to be at the forefront of the political establishment.

😆 🤣 😂

Evangelicals are cheering him on as God's champion.

If he really belonged to Jesus, the establishment would have thrown him out long ago.

RELIGION RUNNING AMERICA:

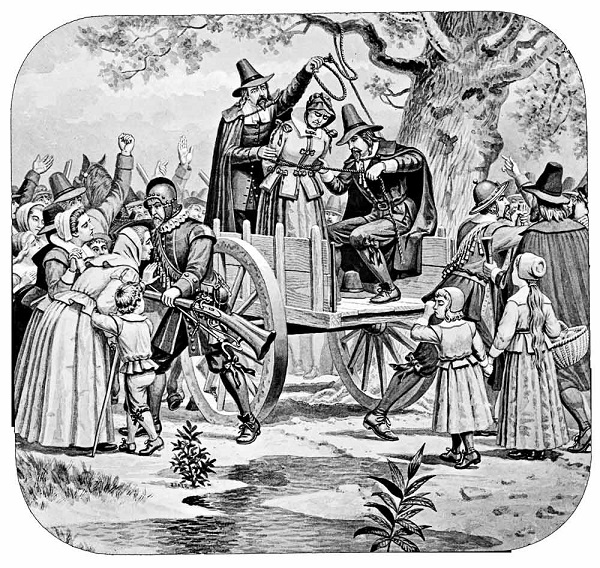

Killing the Witches

Bill O'Reilly & Martin Dugard

The Horror of Salem, Massachusetts

Blinkist: Big ideas in small packages

The story of the Salem Witch Trials exemplifies the enduring role of religion in American life and the threat zealotry poses to liberty. In 1692, accusations of witchcraft consumed the Puritan settlement of Salem, Massachusetts. Religious fervor and paranoia led to the executions of 19 people, mostly women. Though grounded in scripture, this fanatical purge violated all standards of justice.

Salem showed how faith can illuminate but also darken human nature. When extremism goes unchecked, moral panic infects communities. Yet the trials also shaped America's founding ideals of religious tolerance. Their legacy persists as both a cautionary tale and as inspiration for pluralism, illuminating the constant tension between faith and freedom.

Though the Devil still provokes hysteria in pop culture, America is secular. Though it still struggles to reconcile faith and pluralism, it has come a long way from the Salem witch hunts.

Brief overview:

The Salem Puritans believed only their one true faith should exist. They saw it as their duty to severely punish anyone who strayed from their moral laws.

In 1630, a fleet of ships brought even more extreme Puritans to Massachusetts. Led by the English lawyer John Winthrop, they founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony, based entirely on Puritan teachings. The King of England had granted them a charter with the generous allowance that they could interpret religious law however they wished.

Winthrop and Endicott joined forces, making daily life in Salem an exercise in religious devotion and submission. Failing to honor the Sabbath or committing blasphemy brought public whippings, stocks, and banishment.

Some brave souls challenged their authority. But figures like Roger Williams who questioned Puritan doctrine were quickly driven out to more religiously tolerant settlements like the Providence Plantation in Rhode Island.

For a time, Salem's economy boomed thanks to trade. This kept religious tensions at bay. But faced with harsh winters and poor harvests, the zealotry returned. By the 1660s, superstition and fear of the occult ran rampant. Rumors of witchcraft started swirling. Soon, a group of young girls assembled, claiming to be “afflicted” by witches from within the community. They were ready to name names. And the Puritan leaders were more than ready to fan the flames.

The Witch Hunt Begins

Bridget Bishop was no stranger to gossip and suspicion in Salem. The thrice-widowed resident had a taste for colorful clothes that did not fit the Puritan mold. Rumors she had killed her last husband trailed her for years.

In 1692, gossip turned to formal charges. Some of the “afflicted” young girls claimed Bridget's specter had choked and pinched them. Their ringleader was twelve-year-old Ann Putnam. Over the next few years, she would testify against over sixty people. Her mother, her step-cousin Mary Walcott and her servant Mercy Lewis all joined in. Her father Thomas Putnam drafted the legal complaints.

At the “afflicted” girls’ behest, Bridget Bishop was arrested for witchcraft. At her trial, she proclaimed innocence. But as soon as she did, her young accusers started writhing in pain, as if struck by an invisible hand. Pleading, Bridget looked toward the sky – and immediately, the girls' eyes rolled back. To the judges, the signs of her guilt were irrefutable.

After a twenty-minute deliberation, the jury condemned Bridget. On June 10, 1692, she was hanged at Gallows Hill. With her death, the dam had broken. The first execution of a Salem witch had sanctioned the purge to come.

Salem’s hysteria had actually begun months earlier, in the home of its minister, Reverend Samuel Parris. That winter, Parris's daughter Betty and his niece Abigail were stricken with violent fits. Their contortions and garbled screams terrified the village. Witchcraft was suspected immediately.

The girls named three village outcasts as their tormentors, including Parris's slave Tituba. To save herself, Tituba confessed to serving the devil and afflicting the girls. She validated the village's fear of witches with vivid stories of recruitments, spells, and demonic conspiracies.

Tituba's confession lit the spark. In naming other “witches,” she set off waves of accusations aimed at the vulnerable: single women, the elderly, the poor. The zealous Puritan leaders were quick to believe her.

Soon jails overflowed with terrified suspects. Though some questioned the proceedings, including the admission of “spectral evidence” in court, few were willing to speak out. Mass hysteria ruled the day. Bridget Bishop would be only the first of many innocents caught in the frenzy.

Cotton Mather Fuels the Fire

Bridget Bishop was far from the only casualty of Salem’s witch hunt hysteria. Between February 1692 and May 1693, more than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, 19 of which were executed by hanging – 14 of them women. The victims included outcasts but also some respected community members. One old farmer, Giles Corey, died under torture after refusing to enter a plea.

As the death toll mounted, some began questioning the witch hunt hysteria. But there was a prominent Puritan voice silencing the dissenters and reassuring the believers: Cotton Mather.

Few people had as much influence and status in the early colonies as this Puritan minister. Mather was a child prodigy, prominent theologian and prolific writer. He was also the zealous engine driving the trials. He preached the existential threat witches posed to Puritan society and demonized anyone who opposed his view.

At some hangings, Cotton Mather personally quieted skeptics in the crowd. For instance, when Reverend George Burroughs was hung for witchcraft, he recited the Lord’s Prayer – something people believed witches could not do. Cotton Mather expertly twisted the doubts that arose. “The Devil has often been transformed into an angel of light,” he warned the crowd. His smooth assurances allowed the execution to proceed.

Privately, Cotton’s equally prominent father Increase expressed his own doubts. Behind closed doors, the Mathers argued over the ethics of “spectral evidence”. In one piece of writing, Increase expresses his concern that innocent people were being condemned “on the sole testimony of the afflicted children.” But in public, he largely backed his son Cotton.

And Cotton did what he thought was best: hunt witches. In his influential book Wonders of the Invisible World, he insisted torturing witches was a social good, cleansing the land. The real source of his vitriol may have been jealousy toward his father. He craved Increase’s esteem and influence among Puritan society. Stoking hysteria around witches gained Cotton his own fame and power.

Increase did start working behind the scenes to gently criticize the witch hunts. He wrote to the governor advising strict standards for evidence. And he published writings debunking supposed cases of possession as mere illness, suggesting not all accusations were valid.

But his interventions were too little, too late. By Fall 1692, twenty-four Salem residents had died from execution, incarceration or torture and over a hundred languished in jail. With the Mathers' blessing, hysteria had superseded reason, with fatal consequences.

A Specter Haunting America

By autumn 1692, the zealous frenzy fueling the trials in Salem was waning.

Several events combined to halt the deadly prosecutions. For one, the hysteria was raising concerns abroad. News of the injustice reached England, alarming King William and Queen Mary. They began questioning the competence of the colonial leadership that had permitted such brutality.

Massachusetts Governor Phips, though late to act, finally intervened after his wife was accused. He suspended new arrests and released many prisoners. He also formally dissolved the Salem court in October 1692, creating a new body barred from considering spectral claims. Though the overeager Judge Stoughton tried to continue hangings, the executions ceased.

Phips left for England to meet with officials of the crown. Just before he embarked on his journey overseas, he pardoned all those accused of witchcraft. But once he arrived in England, he was arrested. Judge Stoughton, a key figure and proponent of the witch trials, had colluded with colonial administrator Joseph Dudley and other London officials to smear Phips and assume leadership of the colony.

Stoughton wanted to resume the witch trials but he lacked the moral authority to garner much public support. With Phips gone, he wasn’t able to revitalize the fervor that enabled the trials. The accusers were also losing credibility as some admitted lying for revenge or fame. The persecution was over.

Cotton and Increase Mathers emerged stained by their zealotry. Increase stepped down as Harvard president and Cotton was passed over as his successor. Now ex-Governor Phips had allowed Cotton to publish one last biased account defending the trials. But Salem wanted to forget the deadly episode as quickly as possible.

Unsurprisingly, the town couldn’t escape the damage done. Salem’s economy floundered and its stature diminished compared to Boston. The Puritan leaders lost influence after enabling such bloodshed. For the accused who survived and their families, there was trauma and lasting stigma. The dead were buried in unmarked graves, forbidden consecrated ground. Their painful legacy would haunt Salem and colonial America for decades to come.

The American Revolution

Though the Salem Witch Trials ended, dangerous religious divisions remained a part of American life. As the nation slowly secularized, the Puritan old guard clung to rigid orthodoxy. This tension would soon contribute to the American Revolution.

In the middle of this struggle was Benjamin Franklin. Once a loyal British subject, Franklin had seen the Crown's contempt for colonists firsthand. After spending several decades in London, Franklin returned to America in 1775, his allegiance shifting.

In Philadelphia, Franklin helped draft the Declaration of Independence, becoming a founding father. When the British occupied Philadelphia in 1777, he fled rather than be captured for treason.

By 1787, independence was won. In Philadelphia, Franklin attended the Constitutional Convention. Though eighty-one and in poor health, his presence gave confidence to fellow delegates in crafting a new nation.

Earlier in life, Franklin withstood Massachusetts’ heavy Puritan influence. Though he admired some of Cotton Mather’s scientific positions and remembered a pleasant personal encounter with him, Franklin had always rejected the minister’s witch hunt fervor.

In Constitution debates, Franklin drew on memories of the Salem horrors. He believed the persecutions showed that a zealous government unchecked by individual rights could produce disastrous results. Having long advocated for religious freedom, Franklin ensured the Constitution granted liberty for all faiths. He joined James Madison in enshrining this religious freedom in the First Amendment.

Franklin had come full circle – from loyalist to patriot, subject to statesman. His life embodied America’s struggle for self-rule, ensuring no faith dominated another. For Franklin, Salem’s legacy was an argument for separating church and state, and safeguarding individual freedom for all. But he could hardly eradicate the long-lasting influence of religious superstition in America.

Ronald Hunkeler’s Exorcism

Ronald Hunkeler was an ordinary American teenager. But in 1949, terror invaded his suburban life. The thirteen-year-old lived with his family in Maryland, where his eccentric aunt introduced him to séances and summoning spirits.

Strange events began plaguing Ronald's home. Scratching sounds and footsteps tormented him at night. Furniture shook violently around the frightened boy. After seeking psychiatric help to no avail, Ronald's Lutheran parents turned to the Catholic church for a last resort: an exorcism.

The Catholic ritual aimed to expel the Devil from Ronald’s body and soul. Two Jesuit priests recorded the traumatic process daily. Scratches appeared on Ronald's skin, furniture flew across the room, and he spat Latin profanities at his exorcists. After weeks of torment, the clergy finally declared Ronald free of demons.

The church kept the exorcism confidential. But Georgetown student William Peter Blatty learned of the diary. After obsessively tracking down its details, he published his book The Exorcist, in 1971. This fictionalized version of the exorcism turned Ronald into a girl. Though initially unsuccessful, the book became a sensation after the author promoted it on a late night show.

In 1973, director William Friedkin brought The Exorcist to the screen. Bizarre occurrences plagued the set, giving rise to an alleged “curse.” Several cast and crew members died during production and young actress Linda Blair endured real pain during the demanding shoot. The film’s graphic horrors left audiences fainting in terror.

The Exorcist reignited a global terror of demonic possession. Yet it also shed light on the ancient rite of exorcism. Like the Salem persecutions, exorcism aimed to cleanse impure souls believed to be invaded by evil. But while witches were executed, exorcism tried to redeem the possessed.

Ronald Hunkeler remained haunted to his death. When The Exorcist premiered, he worked secretly for NASA. But the film's popularity threatened to expose his past. Teenagers flocked to Hunkeler’s childhood home, believing it was the site of the exorcism. Ronald sank into private turmoil, which continued until his death in 2020.

The horrifying story of Ronald’s exorcism evoked the Salem panic, showing that superstitious beliefs have colored American history for a long time. Whether in 1600s Salem or the 1950s suburbs, the battle between faith and reasons endures.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment